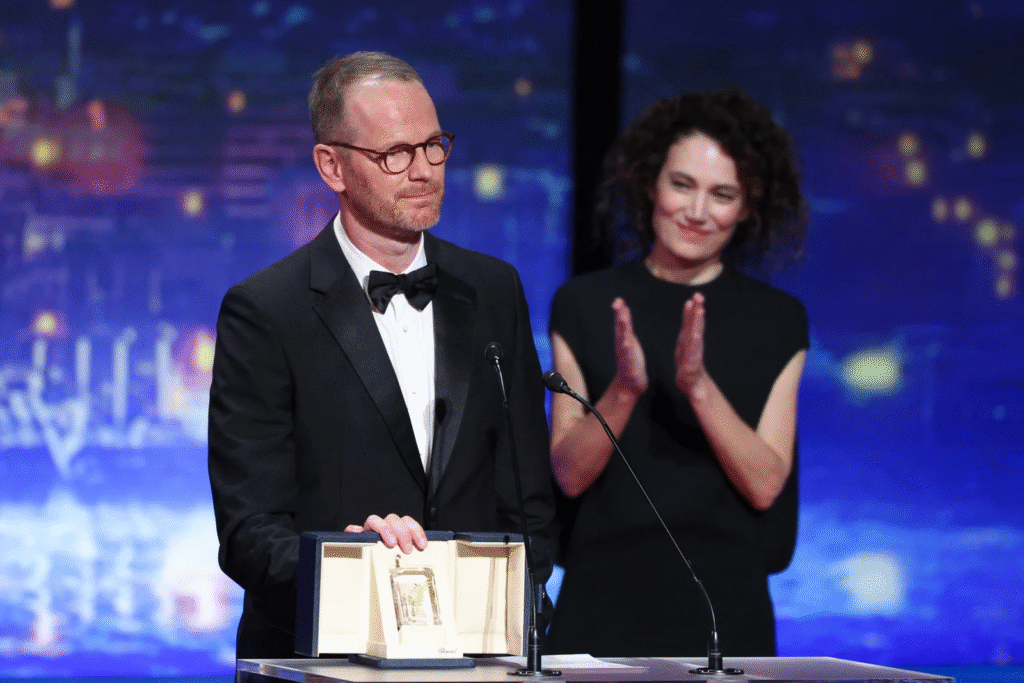

Ahead of the theatrical release of Sentimental Value (2025) later this year, i decided to finally sit down and watch the Oslo trilogy by the same director, Joachim Trier. The Danish born Norwegian filmmaker has recently become one of cinema’s most renowned voices, with success coming both domestically and globally; he was nominated for ‘Best Original Screenplay’ at the 2022 Oscars for The Worst Person In The World (2021) and won the ‘Grand Prix’ (2nd best film) for the his aforementioned film at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival.

Even though it’s dubbed the Oslo trilogy, it’s not really a trilogy; not in the traditional sense at least. We don’t follow the same characters, we don’t follow the same storyline and they’re technically not even set in the same universe. This is more a trilogy of theme. They’re all about growing up. The jump from adolescence to adulthood. The responsibility that comes with this leap and the actual reality that follows it. Trier uses Oslo, Norway as a constant anchor for this trilogy, it serves as a microcosm for the experience of growing up, hence the ‘Oslo’ trilogy.

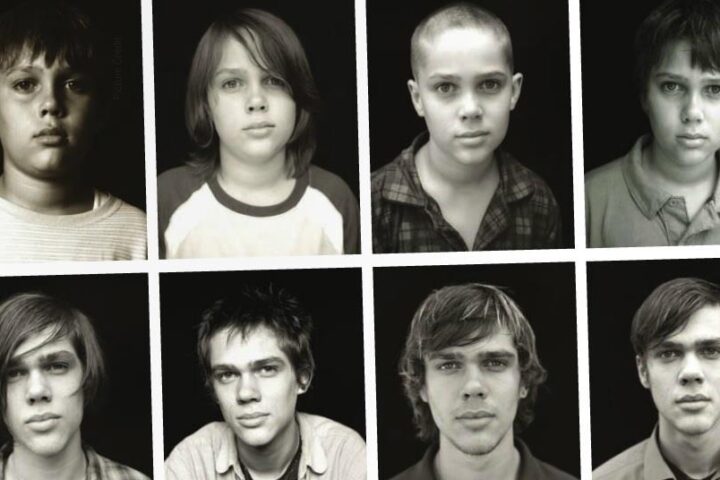

The trilogy consists of Reprise (2006), Oslo August 31st (2011) and The Worst Person In The World (2021). In my opinion, The Worst Person In The World (2021) is the standout of the three but they are all great and i highly recommend them to anyone with even a slight passing interest in film. They are all currently available to stream on Mubi.

WHY?

The Worst Person In The World (2021) is a true masterclass in storytelling. It really is one of the most impressive, contemporary screenplays. It’s actually structured like a book, with the film being divided into different sections (a prologue, 12 chapters and an epilogue). This format is actually what makes it so great. Trier chooses pivotal, specific moments of Julie’s life (the main character) to explore, oftentimes skipping years whilst doing it.

This is quite different to your normal coming of age film, where everything important in the characters life happens over one hazy, romantic summer. Where the meaning of life comes to them whilst sitting on the beach at their school leavers party. Where the chaos of adolescence promptly ends ends and neatly becomes the clarity of adulthood. No, this is not how this film works at all. This is not how life works at all. Trier chooses to show life and growing up as it actually is, even if that means it’s a slow, messy, contradictory patchwork of memories. Trier highlights how going through change doesn’t exactly bring clarity and getting older doesn’t exactly mean you’re growing up. He isn’t trying to tell a ‘story’, he’s trying to hold a mirror to ‘life’.

AUTONOMY VS PRESSURE

The film deals with a lot of themes and topics (identity, time, love etc…) but i think it’s most interesting is the evergoing battle between personal autonomy and societal pressure. Another reason i think this film is a masterclass in storytelling, is how it manages to weave this central theme in to the first fifteen minutes of the screenplay. Trier communicates this theme so clearly, so quickly and in so many different ways. He is a filmmaker entirely in control of his voice. He knows exactly what he wants the film to say and he wastes no time to say it.

OMNISCIENT NARRATION

The prologue opens with a montage of Julie, a late 20’s medical student, played by Renate Reinsve. An omniscient narrator guides us through her life and thoughts. We watch her struggle to find meaning or purpose in the world, she didn’t pursue medicine out of any real passion or desire, she only became a medical student because she feels it’s the only career path that deserves her high achieving grades. It feels like an obvious path for her to follow:

“She’d chosen medicine because it was so hard to gain admission. Where her excellent grades actually meant something“.

The use of omniscient narration here nails home the problem that Julie will struggle with for the rest of the film, will she do what she actually wants or will she do what society have planned for her?

Trier is no stranger to omniscient narration, he actually used it in Reprise (2006), the first film of the trilogy. The fact he has used it in two seperate films shows that this isn’t an excuse to get exposition across easily but it’s actually a deliberate storytelling choice. It helps amplify the feeling that Julie’s life is already mapped out by the powers that be, that the narrator itself is guiding her down a path that they choose. The narration symbolises that even though Julie is aware and cognisant of these external pressures, that they are so deeply ingrained in her subconscious that it’s difficult to escape them, even if she’s actively seeking autonomy and freedom.

MEETING AKSEL

As the prologue continues, we see Julie break up with her boyfriend and change focus from medicine to psychology and eventually settling on photography. It is in this phase of her life, where she attends an industry party and meets Aksel, a relatively successful comic book writer/artist in his 40’s, played by Anders Danielsen Lie, who was actually the lead in the previous two films of the trilogy (FUN FACT: he is actually a licensed doctor and runs a clinic in between acting jobs, how ironic).

After spending the night at Aksel’s, he makes it clear to Julie that he likes her but a relationship between the two would never work:

“If we go on, I’ll fall in love with you. Then it’ll be too late. Maybe we should agree to stop seeing each other. The problem is our age difference. I’m just afraid we’ll fall into a vicious circle. You’re much younger than I am. You’ll start to question who you are. I’m past 40. I’ve entered a new phase. Whereas you still need time to find yourself. You don’t need me waiting. You need to be completely free. I’m just afraid we’ll hurt each other“.

This whole spiel obviously doesn’t work because has it actually ever? They instantly start dating and not long after move in with each other. This act of defiance by Julie to reject Aksel’s ‘wisdom’ just further helps to accentuate the battle she is facing, autonomy vs societal pressures (societal norms in this case).

However, this defiance is so tragic because we know exactly how it’s going to end and so do they, Aksel said it perfectly himself. When being interviewed about the Succession (2018-2023) finale, Mark Mylod, a director and producer for the show , said:

“My understanding of the show has always been that it’s a tragedy. Therefore, every moment of hope is so cruel, because we’re just waiting for that shoe to drop and waiting for their essential nature to be exposed. To break your heart again“.

The same can be said about Julie and Aksel. Their story is inherently tragic because we know how it’s going to end, it embodies the cruel hope that Mylod describes. Both, Julie and Aksel, know their relationship can never ‘actually’ work out, not because of any dramatics but because of who they are and where they are in life. Julie is on a path of reinvention, she is still ‘becoming’. She has everything in front of here. There’s a freedom in that. Whereas, Aksel has already became the person he will be, he has already made his legacy and formed his life. He wants stability and to settle down. They’re caught in an impossible space between wanting to pursue their own paths and wanting to connect with each other. To fully commit to one is to compromise the other.

Trier’s brilliance is on display here . He doesn’t frame their relationship as a tragic failure of love like so many other lazy drama’s do nowadays. Instead, he shows it to be the cost of choosing autonomy in a world that constantly demands compromise. He shows how deeply entangled our desires are with the expectations around us. The heartbreak isn’t just personal, it’s structural. By allowing hope to exist in the same space as inevitability, Trier reveals something profoundly true about what it means to grow up.

QUESTIONS. QUESTIONS. QUESTIONS.

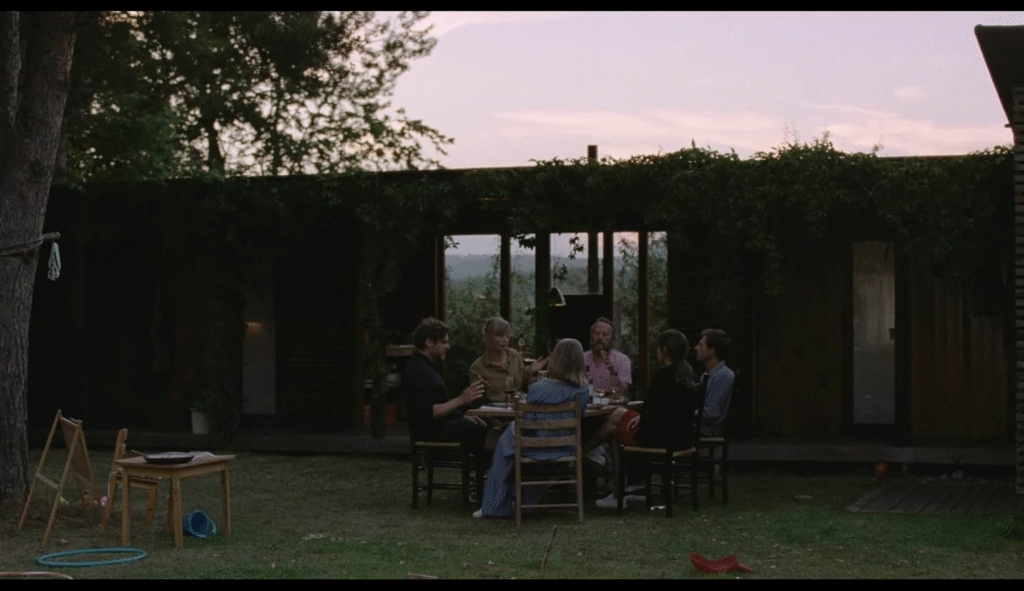

Later on, Julie and Aksel spend the weekend at Aksel’s family home, where they are joined by his brother, sister in-law, mum and dad. Upon arrival, Julie gets politely interrogated by Aksel’s sister in-law. She prods for information about her profession and day to day life. After being clearly uncomfortable, Aksel’s brother steps in and remarks about how asking such questions when they were younger would be considered vulgar.

I think this one of the most interesting lines of dialogue in the whole film. In what seems like a relatively small moment, a huge truth is revealed. Oftentimes, as people grow older they become domesticated of sorts; not just settling down but in how they start to measure and see life. The question they thought was almost disrespectful twenty years ago, has become a weapon they use to judge others. It becomes clear in this moment how the ideas and notions that Julie is trying to resist aren’t always maliciously deployed. Aksel’s brother and sister in-law aren’t evil, they’re not even really aware of what they’re doing. it’s become second nature to them. They’re regurgitating the conversations and pleasantries that they have learned over the years as adults.

What seems like small talk to them feels insidious to Julie; the subconscious expectation of what a ‘normal’ life looks like manifests itself quietly at dinner tables, family holidays and school playgrounds. This is exactly why it’s difficult to combat societal pressure because people end up reinforcing it without really realising. It’s never really presented as a malicious demand, it’s never as simple as someone saying “YOU MUST DO THIS” or “YOU MUST BE LIKE THIS”, it normally arrives as a disguised politeness, as a tradition, as a concern. The question loses its edge to them but it still cuts deep for her. Trier uses this exchange to show the audience how the autonomy Julie craves and searches for isn’t necessarily about making different and zany choices, it’s about trying to live without being measured by someone else’s perception of how your life should be going. Simply, she wants to live her own version of adulthood, without having to justify her choices at every turn. Trier captures really well how hard it is to actually be autonomous; this two minute chunk of dialogue perfectly shows how expectation gets passed down from generation to generation.

I DON’T WANT TO!

Another fantastic exchange of dialogue comes just a scene after this, when Aksel’s sister in-law tries to send her daughter to bed. The little girl runs rings around her mum, loudly refusing her orders; she sprints over to Julie and falls like an anchor at her feet, wrapping her arms around Julie’s legs.

“I don’t want to!” The little girl cries.

“But i want you to!.” Her mum replies.

This scene serves as a perfect microcosm for Julie’s current situation. On the surface, it’s just a classic game of cat and mouse between a mum and kid. The kid wants to do anything but whatever the mum is asking them to do. However, beneath the actual action is a very apt metaphor. It’s the exact same tug of war Julie finds herself in; the battle of what you want vs what others want.

Julie stands completely still during this scene, almost as if she’s frozen in place. The camera focuses on her expressionless face and its in this exact moment something clicks. She recognises herself in the little girl. Not just because she used to be like that but because, deep down, she still is that girl. The defiance, the discomfort, the instinct to resist being told what to do. It’s all still alive in her, just buried under layers of adulthood, expectation and silence. It’s not nostalgia she feels but recognition. This isn’t a memory, it’s a mirror.

Trier not only uses this quiet moment to reinforce the theme of autonomy vs pressure but to also make a statement regarding it. The battle for self and autonomy doesn’t stop when you get older, in fact it gets more nuanced and complex. Oftentimes harder.

BUT I WANT YOU TOO!

In the very next scene, the theme of autonomy vs societal pressure becomes a lot more obvious. It’s very on the nose, the pressure manifests more explicitly. It’s an argument. Julie and Aksel bundle themselves into a small guest room in Aksel’s family home after spending the day with his nephews and nieces. Aksel tells Julie about his desire to have his own kids soon and how he is only getting older. He feels ready to be a father and live a family lifestyle. Julia’s resistance is palpable and rightly so; her boundaries and hestitance regarding children was known by Aksel from the very start of their relationship. Julie gets annoyed at Aksel’s relentlessness:

“I didn’t want to get into this, really not… Everything’s on your terms. You have time off, so we’re on holiday.”

“You agreed.” replies Aksel.

“After you publish, you get bored and start talking about kids. The others here have kids so it’s an issue.“

“Not true.” he argues.

“It is true. And then you get a new idea at some point and disappear into your drawing board.”

This conversation is not just about whether they should have kids or not, it’s about whether this is the life she actually want to be living or is she just being swept along by the tide of what’s expected of her by Aksel and on a more grand scale, society.

It becomes abundantly clear in this moment, how little control Julie has over her life, even after make a specific attempt to be in control. The flood of pressure from Aksel, family and society is overwhelming her because of course it is! Nothing is on her terms. She is a passenger in her own life.

The scene ends with an incredibly striking visual that reinforces my previous point of Julie recognising herself in the little girl. After the heated argument, Julie and Aksel both climb into different levels of a bunk bed… The only room left in the house for them was a room with a bunk bed. This is not a random choice by Trier. When you’re a kid having a bunk bed might be the coolest thing you can have but Julie and Aksel aren’t kids. Watching her climb the ladder onto the top bunk almost feels a bit degrading. Humiliating. She is metaphorically being reduced to a child because the world surrounding her doesn’t think she is ‘ready’ to become an adult.

There’s also another metaphor in play here; Julie climbs onto the top bunk, whilst Aksel falls onto the bottom. It’s a simple image but says quite a lot. They aren’t on the same level. Not emotionally, not mentally, not even on the same bed!

3 DIFFERENT LEVELS OF THE SAME BATTLE

All these scenes happen within the first fifteen minutes of The Worst Person In The World (2021)! Trier masterfully establishes the film’s central theme, personal autonomy vs societal pressure and manages to explore it on three different levels; Within society, family and romantic relationships.

In just fifteen minutes, Trier lays the emotional and thematic groundwork for the next two plus hours. That is exactly why The Worst Person In The World (2021) is one of the best contemporary screenplays about. Not many films can say so much, so early and still have so much left to show. Trier is a genius and i can not wait for Sentimental Value (2025).

Be sure to keep up with all our latest essays, analysis’ and reviews and within the film and tv industry by following our social pages and checking out our blog page.